Car companies across the world are all feeling the pressure of the current battery supply chain. VW have even just announced that they have “run out of EVs” for this year. Some musings in a battery conference left me thinking about some of the opportunties upstream and what we can do to secure battery supplies. Cue a tenuous food related analogy….

Imagine for a moment that the world collectively agreed that eating a slice of toast every day was an essential part of a healthy lifestyle. Then imagine that in actioning that plan we discover that over 90% of the world’s bread industry – from growing the wheat, making yeast, making flour, manufacturing ovens to bake the bread, baking the bread and shipping it, was concentrated in China. Suddenly a single market could control the global price and supply of bread whilst also leaving a gaping hole of dough related skills elsewhere in the world.

One of two scenarios might unfold.

Supermarkets and restaurants outside of China spot the opportunity. To hedge their bets, they start securing supply at source, or partner with farmers to make their own local wheat farms. After much campaigning from new bread makers and suppliers, as well as from consumers who want a healthy lifestyle enabled by bread (we can dream), governments respond with funding and policies to support bakeries, farms, and associated skills development.

Alternatively, nothing changes, and the industry remains concentrated in China who spotted the bread trend 5 years earlier (at least) than the rest of the world. Demand outstrips supply and bread becomes a luxury item reserved only for the mega rich or extremely special occasions. Reaching our healthy lifestyle ambitions remains a pipe dream reserved for the minority of wealthy individuals who can afford it.

Yet this is the situation we find ourselves with batteries for electric vehicles. Swap out the term “eating a slice of toast” for “driving an electric car”, wheat and flour for “battery raw materials”, supermarkets and restaurants for “OEMs and Cell Manufacturers” and healthy lifestyle for “good air quality” and once again we have a laboured analogy that hopefully sort of does the trick.

Today we know we need electric vehicles to hack away at the 30% of global CO2 emissions that transportation currently ladens on our fragile planet and governments and OEMs have made commendable targets to realise that future. Battery production in Europe is expected to grow sixfold by 2030 with similar growth expected in the US. In Europe this would put planned annual capacity at 789.2 GWh in 2030, enough to produce almost 15 million EVs – 14% of the global total.

But what’s feeding these gigafactories? Ingredients for batteries, which so far truly are > 90% concentrated in China. Most notable of those ingredients are Graphite (29% of battery cell by mass) either Nickel, Manganese and Cobalt for NMC cathodes, or the cheaper and increasingly popular Lithium, Iron, Phosphorous for LFP Cathodes. In short, there is a bulge slap bang in the middle of the supply chain – we’re building multiple bakeries and still relying on a single source of flour.

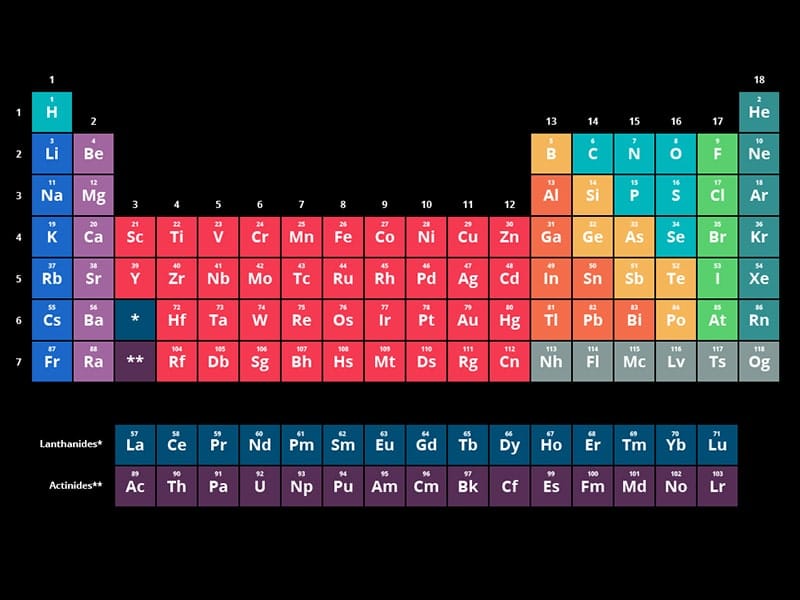

This challenge was made abundantly clear to me at the recent “Battery Megafactories” conference in Berlin. Having worked in the automotive industry for the best part of a decade I have witnessed it go from traditional OEM to the emergence of start-ups forcing automakers to reposition as “tech companies”. Goodbye suit and tie, hello branded t-shirt and Veja trainers.

Walking into the Berlin Battery Megafactories Conference, therefore, was like walking back into 2014. Not a trainer in sight and a volume of ties now only seen at weddings and funerals. What this told me is that the delegates in the room were representing industries that maybe don’t seem appealing to a TechCrunch reading audience and most likely aren’t attracting the 20 something engineering graduate who wants to change the world. These delegates were from mining, battery material companies and cell manufacturers – the industries that hold literally all the cards to making electric vehicles at scale a reality. In other words, this was the difference between an Ottolenghi masterclass at Daylesford and a wheat farmers’ social in Chipping Norton.

Over the course of the two-day conference not only did I see a grand total of 7 women, but I learnt four key things:

- Since 2014 the cost of a battery has come down from $280 per Kwh to $114 per Kwh which now means that 70-80% of that cost is raw materials. Despite that, investment upstream of cell manufacture is half of that downstream.

- Generally, stakeholders involved in the battery supply chain would like to prioritise environmental metrics, but security of price and supply end up taking precedence to avoid consumers being burdened with a higher purchase cost of their electric vehicle.

- Mining is the one almighty elephant in the room. The mining industry can have transformative effects on local communities and the environment, but those effects can be both overwhelmingly positive or negative. The location of raw materials is so often in geopolitically challenging areas which is in large part what makes them geopolitically challenging in the first place. We must do more for transparency, accountability and human rights whilst still operating profitably.

- Meeting future battery demand is going to take a combination of diversifying the supply chain across the world and pioneering new battery recipes to improve performance that would help reduce the dependence on our current key ingredients.

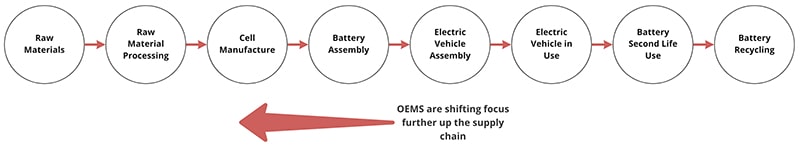

As bread scenario 1 outlined, to mitigate these risks OEMs and Cell manufacturers are getting involved further and further upstream. In January Tesla signed a deal to procure 80% of its graphite from one of the world’s largest graphite mines in Balama, Mozambique which is operated by Syrah Resources and more recently secured three years of lithium from Gangfeng Lithium. Two weeks ago, VW announced a joint venture with Huayou Cobalt and Tsingshan to secure nickel and cobalt supplies in a bid to reduce costs and secure supplies. GM, Toyota and Ford are all making similar moves and with Biden triggering the Defense Production Act to secure U.S. sources of battery raw materials to ramp up US battery production – there are bound to be a wealth of additional material scrambles.

But whilst the game of raw material hoarding unfolds there are a tonne of companies forging a new status quo upstream. In bread terms, they’re striving to make sure the bread has even more nutritional value whilst being fairly and locally farmed.

Snowlake Lithium is creating a fully electric and 100% renewable energy powered Lithium mine in Canada to provide US EV manufacturers. Storedot, Nexeon and Sila as well as sounding like Avengers, are also developing silicon anodes which would substantially increase the amount of energy a battery can store (the capacity). This in turn would enable smaller batteries for the same application and mean other battery raw materials could make more batteries too. (see this blog for a different food analogy to explain how this works). Sheffield based Faradion is using Sodium, literally table salt, instead of Lithium for batteries for energy storage systems. Theion has developed a sulphur-based cathode that claims to triple energy density and uses substantially less energy to produce. Incidentally they’re also pioneering solid electrolytes, but I’ll save that for another time.

Finally graphite processor Urbix recently announced its plans to expand to the UK. Urbix is processing raw graphite and turning it into the catchily named CSPG – Coated, spherical, purified graphite. These tiny balls of processed graphite are the product of a novel processing technique that uses a fraction of the energy, acids and physical space used in graphite processing plants in China. This may not sound that exciting but currently we have the crazy situation of creating synthetic graphite in the UK, shipping it to China for processing and shipping it back to turn it into battery cells. Back to the bread analogy and that’s the equivalent of growing wheat in the UK, sending it to China to make it into flour and bringing it back to the UK to bake it into bread. That’s an awful lot of middlemen.

Last week I sat in the All-Party Parliamentary Group critical minerals roundtable tucked away in the attic of the houses of parliament. As I sat there, also amidst a distinct lack of Veja trainers – it struck me that if I was 17 and applying for engineering – this is where the opportunity lies.

Bread is possibly more compelling than a whistle stops tour of the periodic table. To reach electrification at the rate and resiliency we want across the world, it’s time for the materials scientists to take centre stage and for those up and down the battery value chain to rally around them. In other words, start making battery recipes as exciting as comparing sourdough starter cultures.

About the author

Imogen Pierce works in sustainable mobility and future technology for Fully Charged. She is an alumni of electric vehicle startup Arrival where she was Head of City Engagement and Integration working with cities to understand, develop and accelerate their future mobility ambitions. Imogen has also worked in Experience Strategy looking at future technology and mobility trends. Prior to Arrival, Imogen was an aerodynamicist at Jaguar Land Rover before running the company’s technology and innovation communications. She can be found on Medium musing and wittering about sustainable mobility.