When the automobile was first invented in the late 19th century there was a smorgasbord of propulsion systems battling it out to dominate the future of motoring.In fact, in 1915 there were 37,000 electric vehicles on the road in the US with many agreeing that electric cars surely had to be the winning choice.

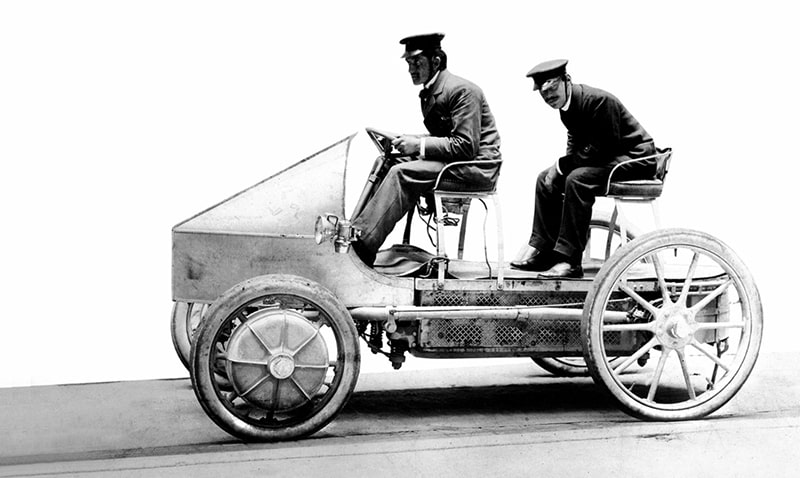

In 1898, Ferdinand Porsche designed the Egger-Lohner C.2 Phaeton. The vehicle was powered by an octagonal electric motor, and with three to five PS it reached a top speed of 25 km/h.

They were quieter, cleaner and as Dr Charles P. Steinmetz said in 1914 in a report to the Electric Vehicle Association

“the electric car is superior to the gasoline car in control and intrinsically more reliable”.

Thomas Edison had an EV, Ferdinand Porsche designed hybrid and electric cars, commercial electric taxis were operational in New York and even Henry Ford’s wife Clara had an EV.

Early 20th century electric cars came with fascinating lease models that included servicing and even a garage near the driver’s property, all managed with a straightforward payment plan. Electric vehicle dealerships of the time demonstrated “the quiet running machines” surrounded by “little clumps of foliage here and there, like oases in a desert, sheltering dainty tea tables”. 1914, or the Genesis and Polestar stores in Battersea Power Station in 2023?!

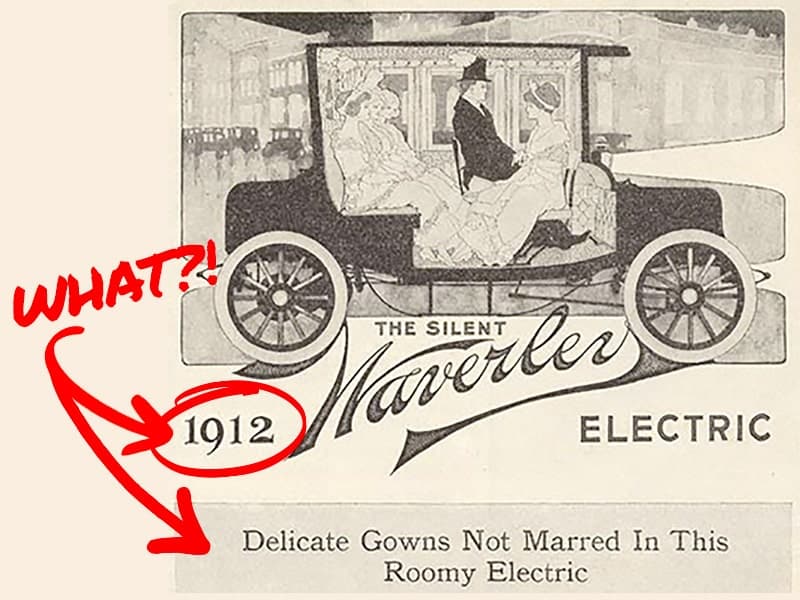

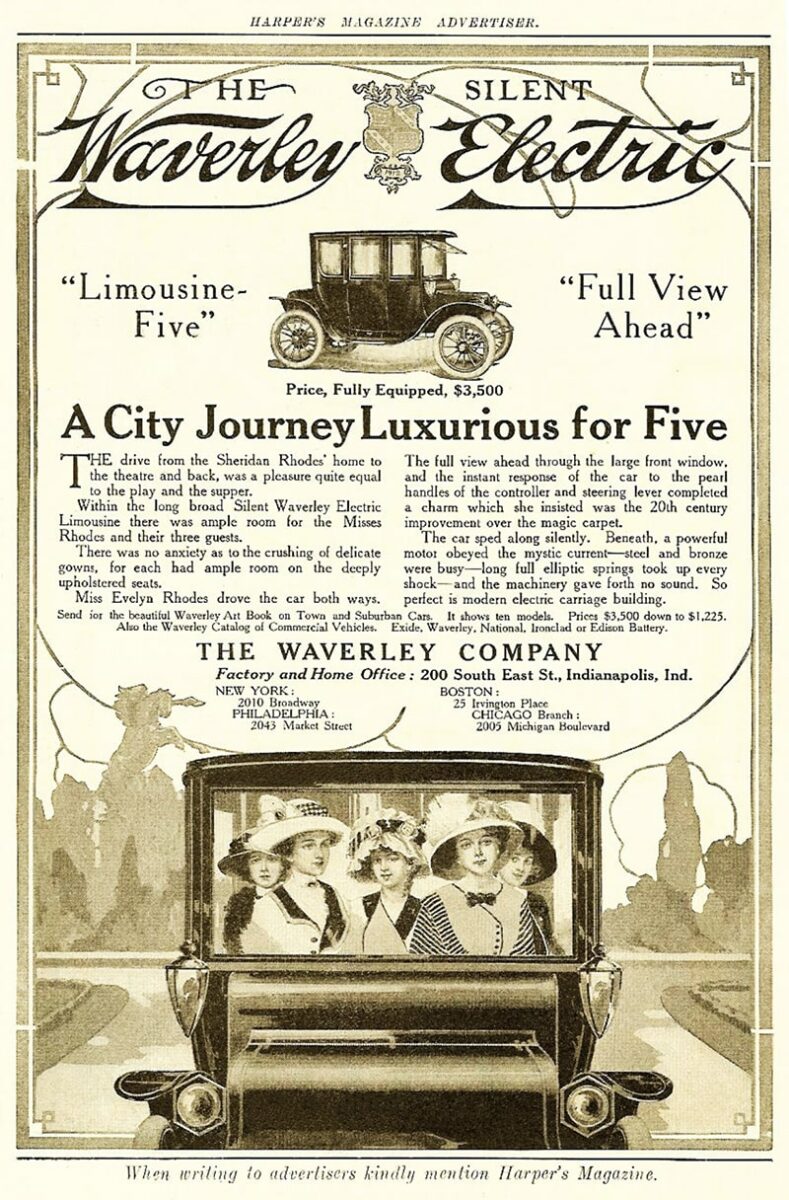

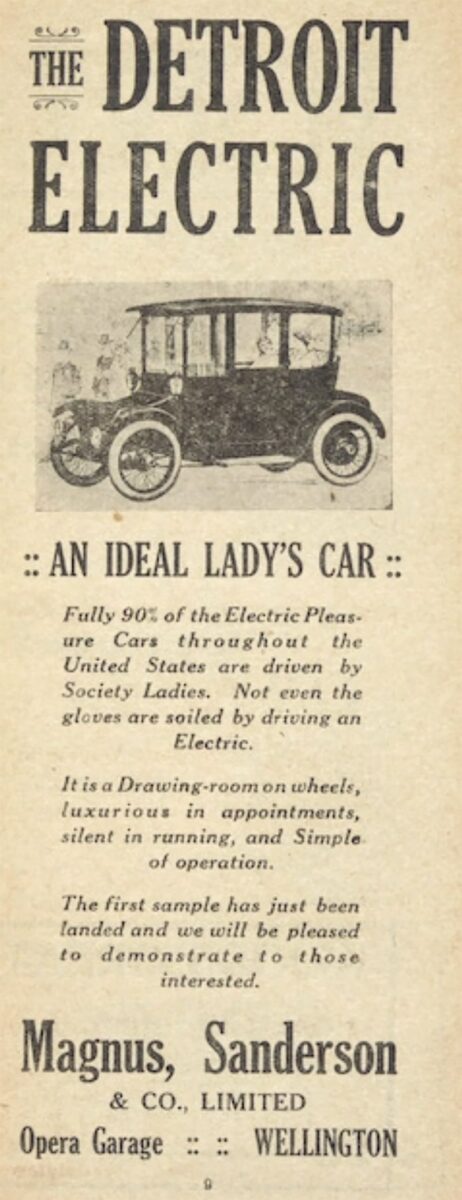

Why then, did gasoline eventually send 20th century electric vehicles into hiding? Well, the answer is not entirely straightforward. Admittedly, combustion engines saw big step changes in performance, petrol got much cheaper and Ford’s Model T accelerated gasoline’s eventual dominance. However, this is in part down to electric vehicles being largely regarded as women’s cars. The Detroit Electric was described as an “ideal lady’s car” and as a “drawing room on wheels” (a notion that has returned to the fore in the form of autonomous vehicles..). The Silent Waverley meanwhile offered “no anxiety to the crushing of delicate gowns”. Men, instead of capitalising on the chance to avoid the “grease, mess and noise of fuel powered cars” by going electric, were marketed the challenge of gasoline motoring and all the macho displays of turning the crankshaft that they offered. Since most middle income households could only afford one car, the patriarchal desire for power and performance won and lo, we endured over 100 years of petrol powered furore.

Fast forward to today and electric vehicle ownership is dominated by men despite women’s earlier preference for them. In the UK, as of November 2021, 76% of respondents driving an electric vehicle identified as men, with 23% of respondents identifying as women. It’s a similar story in the US and even in China where EVs make a bigger proportion of vehicle sales. This shouldn’t come as any surprise, it wasn’t the technology that women preferred in the early 1900s, it was the freedom, ease of use and pragmatism they afforded, contrasted by their male counterparts’ enthralment with gadgets and gizmos. On the whole, that is an attitude that, and please forgive the extraordinarily broad brush I’m about to use, has transcended all time and technologies.

You can find all manner of studies out there that draw a similar conclusion. Men tend to be more image conscious and let emotion influence their car choice, whereas women tend to be more utility minded. It is no wonder that women mostly have the final say in the eventual purchase.

However, electric vehicles definitely aren’t lacking utility. They are often as durable, reliable and affordable to run, as they are decked out with technology and exterior styling and other factors prioritised by men. Increasingly granular marketing insights make it easier for car companies to better understand and target their female customers but that still doesn’t mean it’s as simple as making the “bro-lectrification” EV pick-up truck adverts witnessed at the superbowl more inclusive. There are a whole host of complex dynamics at play.

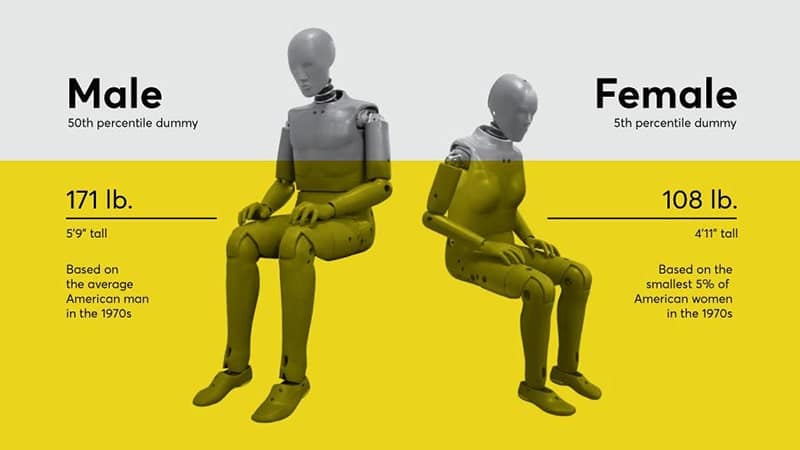

First and foremost, the car industry is extremely male dominated with over 70% of roles held by men. We are all familiar with the various problematic consequences this has had from a safety perspective such as crash standards being set around male crash test dummies. This imbalance is a challenge that has its roots in STEM participation in school generating a pipeline issue of talent and a whole myriad of other challenges around perception of the industry and working culture. I’m greatly encouraged every time we visit a company, school or university genuinely committed to diversity and inclusion initiatives to improve the opportunities for current and prospective students and employees.

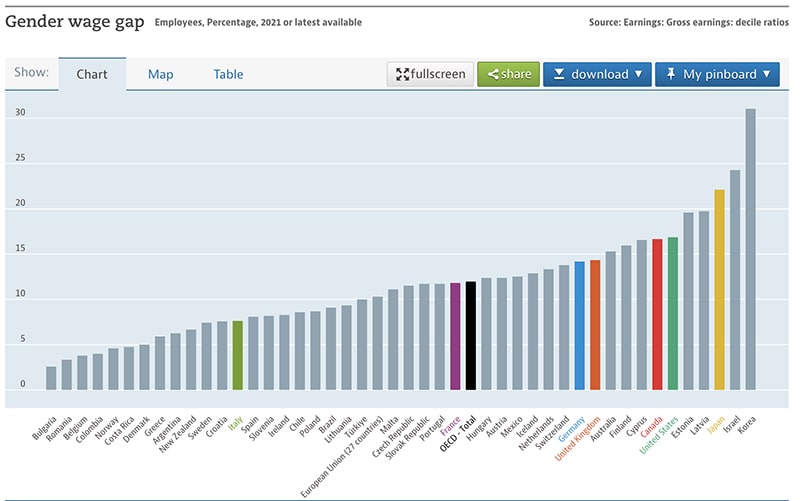

But perhaps more pertinent for EVs specifically is the price point. Electric vehicles are currently more expensive than their petrol and diesel equivalents and, unfortunately the gender pay gap is real, in part due to the eye watering cost of childcare which takes so many women out of the workforce at critical points in their careers. We also know that women’s travel patterns tend to involve more trip chaining than men, where journeys incorporate additional stops for caregiving and household activities as well as commuting. Trip chaining in an EV likely requires a greater dependence on the public charging network and therefore represents an additional step of planning, instead of relying on comparatively easier and often more reliable destination charging at home or work. In the UK we have a problem with perceived safety at public charge points, 87% have poor lighting whilst 77% don’t have security cameras, factors which greatly contribute to women in particular feeling unsafe when waiting to charge. These concerns are felt even more acutely in lower income areas where off-road parking is more limited and the public charging network less abundant.

These barriers to electric vehicle adoption are not insurmountable, but they do exist and disproportionately affect women. If we want to drive EVs into the mainstream, they have to make sense for all drivers. In a few week’s time we’re meeting the Osprey team who are working with ChargeSafe to make more accessible and safer charging locations and we’re lucky to meet a whole array of exceptional companies tackling these meaty challenges. We get to interview incredible women and allies pioneering change across the industry but it also highlights to us the major gap in women represented in the automotive industry and green tech jobs more broadly. Numerous studies have shown this to be hugely problematic in the fight against climate change, with Project Drawdown concluding that gender equity and representation is vital for effective climate policy.

Fastned has pioneered accessible charging

According to UN Women,

“Women commonly face higher risks and greater burdens from the impacts of climate change in situations of poverty, and the majority of the world’s poor are women. Women’s unequal participation in decision-making processes and labour markets compound inequalities and often prevent women from fully contributing to climate-related planning, policy-making and implementation.”

It goes on to say,

“Women’s participation at the political level has resulted in greater responsiveness to citizen’s needs, often increasing cooperation across party and ethnic lines and delivering more sustainable peace. At the local level, women’s inclusion at the leadership level has led to improved outcomes of climate related projects and policies. On the contrary, if policies or projects are implemented without women’s meaningful participation it can increase existing inequalities and decrease effectiveness.”

Better decisions come from diversity of thought; where pragmatism, empathy, inclusion, excellence and innovation are valued equally. That can only come when all voices are represented and respected.

So let this International Women’s Day serve as a gentle reminder to be an advocate and an ally to all people so that we can make the very best climate solutions. Otherwise we risk the next 100 years being determined by the consequences of showing off brute strength as we did with the crankshaft that landed us in this mess.

About the author

Imogen is a presenter and producer for “Halo” Content on the Fully Charged SHOW where she focuses on the latest and greatest innovations across renewable energy, sustainable mobility and future technology. She is an alumni of electric vehicle startup Arrival where she was Head of City Engagement and Integration working with cities to develop and accelerate their future mobility ambitions. Imogen also led the startup’s Experience Strategy identifying future technology and mobility trends. Prior to Arrival, she was an aerodynamicist at Jaguar Land Rover before running the company’s technology and innovation communications. Imogen graduated from the University of Oxford with a First Class degree in Mechanical Engineering but has since found she is much better at talking about engineering than actually doing it!