Polestar joins Storedot as a strategic investor

Polestar is the latest partner to join StoreDot’s mission of extreme fast charging, starting with 100 miles of range in 5 minutes of charging. But do we need it?

Lithium Ion battery packs are made of cells and cells are made of a cathode, an anode and a liquid electrolyte that sits between them. Electrons and positively charged ions flow back and forth between the cathode and anode depending on whether the battery is being charged or discharged.

With the race to electrification well and truly underway, scientists and engineers are turning to battery chemistries in order to make cells from more abundant materials, cram more capacity into the same space, make batteries smaller or able to charge more quickly. Amidst burgeoning supply chain concerns, innovations in the cell are gaining more and more attention.

The trouble is, if this was easy we’d have cracked it already. Battery materials exist on the 0.001mm scale and cells exhibit some pretty wild properties. Lithium can get involved in side reactions either reducing the capacity of the battery over time, or forming dendrites that can damage the safety of the cell. Slow charging is like Lithium ions forming an orderly queue to enter the anode, whilst fast charging can be like those ions barging aggressively through the door. Charging profiles are strange and non-linear with the rate of charging being entirely dependent on the current and the state of charge of the battery.

In recent months the likes of StoreDot, Sila nanotechnology, Nexeon and Group14 have burst onto the stage with an array of strategic partnerships and the promise of silicon dominant anodes to solve the various battery woes. Last week Sila announced its material would appear in the Mercedes G-Class in 2025 and Group 14 raised $400 million in a funding round led by Porsche. Silicon offers substantial capacity increases but as it is prone to expansion, thus novel anode structures must be pioneered to prevent silicon going full Violet Beauregarde every time the cell is charged.

A brief glance at StoreDot’s website and given their technology, you’d think worrying about battery cells was a waste of time. According to CEO and Cofounder Doron Myersdorf, the team are

“working on the key element which is the anode active material and we are replacing the traditional graphite with our nano-silicon composite with carbon and some organic additives, in order to enable fast charging, meaning extreme fast charging – that is charging in minutes”.

Doron believes that extreme fast charging is the answer to tackling range and charging anxiety.

“An electric vehicle is already a much better driving experience but people still get concerned about access to chargers or range – and that’s what we’re here to solve. We’re not the only ones using silicon, but we are the only ones looking at it for extreme fast charging.

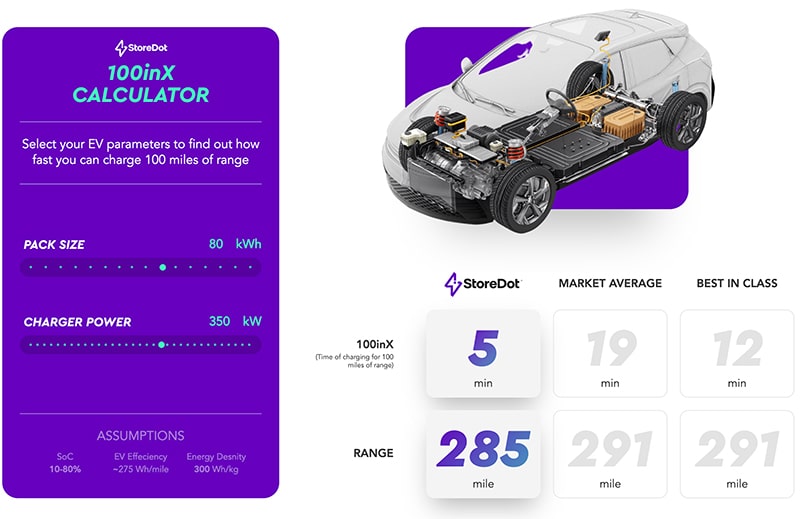

The team recently held a live demonstration showing the capability of charging 100 miles in 5 minutes (0-80%) based on available StoreDot pouch cell battery technology. The milestone was a significant step in the company’s vision of equipping EVs with 100 miles in 5 minutes of charging by 2024, 100 miles in 3 minutes by 2028 and 100 in 2 minutes by 2032.

Storedot can offer 100 miles range after 5 minutes of fast charging

It is no wonder that luxury car marque Polestar is the latest strategic investor to join the StoreDot journey. 100 miles in 5 minutes is effectively the same user experience as fueling, and as such represents a highly attractive prospect owing to the minimal behavioural change required from drivers. However, this illustrious goal can only be achieved with fast charging at powers over 350KW. For current petrol station locations to have a chance of survival beyond 2030, they not only need fast chargers but also an advanced technology for batteries that can charge very fast and that are compatible with high power charging. Unsurprisingly therefore BP, who has over 18,500 petrol stations, is another member of StoreDot’s strategic partners.

“BP realised someone has moved the cheese – they don’t want to be like Kodak and they saw back in 2018 that they needed to totally reinvent themselves for charging instead of fuelling. The whole forecourt model cannot work if charging is not in minutes – not only the real estate but also the retail – if you buy a cup of coffee and sit for three hours, even if you also bought a falafel – it doesn’t work as it has to be minutes in and out.”

Doron commented on the relationship between StoreDot’s technology and charging infrastructure.

StoreDot’s ecosystem of partners is far reaching and impressive. Between Daimler, BP, VinFast, Volvo, Ola Electric, Samsung, TDK, EVE Energy and now Polestar, it is tapped into a substantial chunk of the ecosystem. This network can both inform the design and evolution of its battery products as well as create the environment that best supports StoreDot’s operation.

Fast charging is not necessarily a silver bullet. Upgrading petrol stations with 350KW chargers would likely require substantial cooling, power upgrades and grid balancing. It’s also a more expensive way to charge and at present, silicon-based anodes do come at a price premium. However, there are use cases, particular journeys, geographies and climates where a 5-minute turnaround makes a lot of sense.

Storedot battery cells

Until recently, I’d barely heard of StoreDot and now not a week goes by when a press release touting a new development doesn’t land in my inbox. It’s surprising therefore that actually StoreDot has been squirrelling quietly away for the past decade trying to find the elusive combination of materials and structure that can dramatically accelerate ion diffusion into the anode for stable extreme fast charging over thousands of charging cycles. I asked Doron how the tipping point that seemingly accelerated StoreDot’s progress had been reached and whether Artificial Intelligence had played a part.

“For years we had 35 PhDs working really hard, and there was some frustration. Essentially two faculties worth of researchers practically doing one thesis – this is an enormous research power. We were stuck at 150 to 200 charging cycles for a number of years and really you need to have a critical mass of data before you can start employing the machine learning tools that will highlight the best formulations. Because no human can look at all the data – every second we’re uploading data and so we have petabytes of it sitting in the cloud, but for this to be valuable for machine learning you need a critical mass of sufficient data from experiments that are alike. Over time we built a state-of-the-art database and in the last two years we crossed this threshold of getting value from our historic data with machine learning and that’s also helped more intelligent design of experiments. That’s what tipped us from a few hundred charging cycles to over a thousand cycles which is really, you know “wow”.”

For me, it is this sentiment that is the most exciting part of StoreDot and is resoundingly cause for optimism. There remain some enormous technical hurdles as we embark in earnest on the road to electrification that will only be solved by bringing together the right partners, combining different scientific disciplines and rallying around a clear vision of the potential impact of a solution – even if realising that vision sits far out on the horizon.

“You have to keep the vision and know this is possible, we will crack it. Keeping the business going based on a scientific vision, it’s been a wild ride.”

Storedot pouch cells

About the author

Imogen Pierce works in sustainable mobility and future technology for Fully Charged. She is an alumni of electric vehicle startup Arrival where she was Head of City Engagement and Integration working with cities to understand, develop and accelerate their future mobility ambitions. Imogen has also worked in Experience Strategy looking at future technology and mobility trends. Prior to Arrival, Imogen was an aerodynamicist at Jaguar Land Rover before running the company’s technology and innovation communications. She can be found on Medium musing and wittering about sustainable mobility.