With just days to go before COP26 starts we are lifting the lid on what on earth is COP, what does it mean and what we should expect from this year’s summit.

Who, what and where

Scheduled to take place in 2020 and postponed due to the Coronavirus pandemic, from 31st October to 12th November 190 countries will descend on Glasgow, Scotland for COP26. The 26th Annual meeting of the UN Climate Change ‘Conference of Parties’ (COP) will convene world leaders, tens of thousands of negotiators, business leaders, government representatives and members of the public to reach an agreement on what to do about climate change. This year’s conference has been jointly organised by the UK and Italy, who hosted several pre-cop events in Milan including Youth4Climate and Pre-COP. The summit has been led by COP26 president Alok Sharma, who was previously Secretary of State for BEIS.

Format

COP26 will take place in Glasgow’s Scottish Event Campus, a winner of the Gold Green Tourism Award and home to five enormous exhibition spaces. The various COP events and areas are divided between the Blue Zone and Green Zone. Access to the Blue Zone is restricted to individuals and organisations recognised by the ‘United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change’ (UNFCCC) of which COP is the decision making body. As well as governments, recognised bodies may include civil society groups, professional bodies, research organisations and public sector alliances. Within the Blue Zone are the highly secure rooms where the government negotiators will meet to discuss national positioning, posturing, alliances and relationships required to meet climate goals.

Conversely the Green Zone is open to the public and will include a wide array of exhibitions and panel discussions to stimulate climate change awareness and engagement. The full programme of Green Zone events can be seen here.

But what actually is COP and what is it trying to do?

The Conference of Parties (COP) are the signatories, or decision making body of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) who meet annually to discuss progress and plans to meet the convention. The UNFCCC was a treaty agreed in 1994 between 196 Countries and the EU, and set the lofty goal of stabilizing greenhouse gas concentrations “at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic (human induced) interference with the climate system”. Importantly it stated that such levels “should be achieved within a time-frame sufficient to allow ecosystems to adapt naturally to climate change, to ensure the food production is not threatened, and to enable economic development to proceed in a sustainable manner”. In 1994 there was substantially less evidence to support the human impact on the environment than there is today, aware that this might not always be the case, the UNFCCC made sure that it “bound member states to act in the interests of human safety even in the face of scientific uncertainty”.

Then came the 2015 Paris Agreement, the 1.5°C limit on warming and NDCs

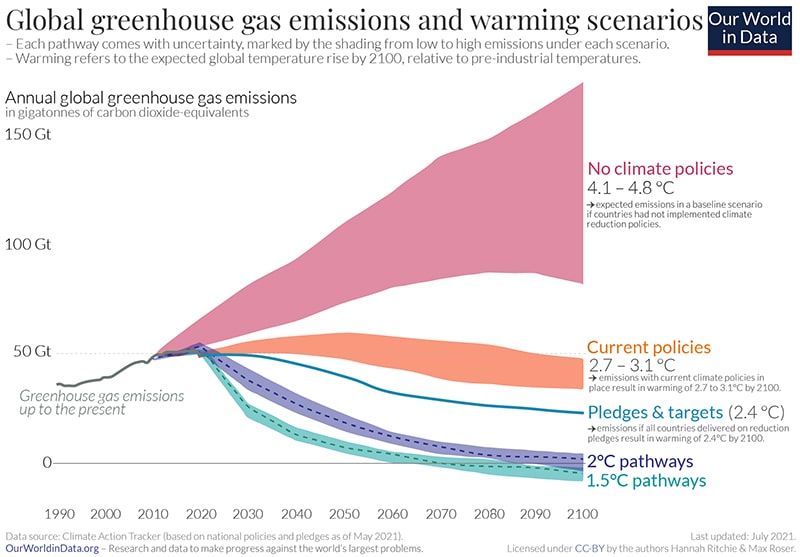

2015’s COP21 was a landmark event in which the Paris Agreement was reached, a legally binding treaty to limit global warming to well below 2°C and preferably 1.5֯°C compared to pre-industrial levels. Since 2015, 190 countries have formally solidified their support. This was an overwhelming success, not least because in Copenhagen at COP15, a limit of 1.5°C was regarded as not only infeasible, but a distraction. However, prompted by growing concerns from the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) who feared extinction if the warming limit was not reduced; a UN Report concluded after consultation with 70 scientists that the previously assumed 2°C limit to warming was indeed ‘inadequate’. Various emissions pathways have been modelled which show that limiting warming to 1.5 °C by the end of the century would require reaching net zero emissions by 2050.

To achieve this long term temperature goal, countries agreed to aim for achieving net zero emissions by 2050 and would lay out their plans to do so via Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) which would be monitored, verified and publicly reported in a bid to make nations more ambitious and accountable for their climate pledges. NDCs will be measured via a “Global Stocktake” to assess progress towards reaching the Paris Agreement. As well as actions to reduce GreenHouse Gas (GHGs) emissions in both the near and long term, the NDCs must also lay out plans to build resilience to adapt to the impacts of climate change and indicate how much financial support developed nations will give to lower income countries to support their climate change efforts.

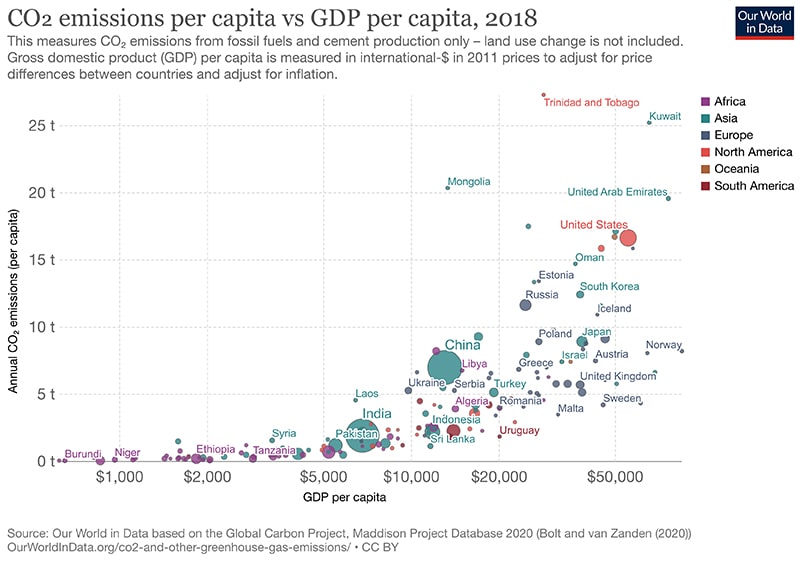

This latter point is in recognition of the fact that many developing countries and small islands are among the smallest contributors to global warming and yet are most acutely suffering its consequences without the necessary means to mitigate and build resilience against climate change. The requirement for financial support to create equity focused climate goals builds on the commitments of the 2009 Copenhagen Accord, which aimed to reach $100 billion of climate finance per year by 2020 for developing nations.

So why is COP26 particularly important?

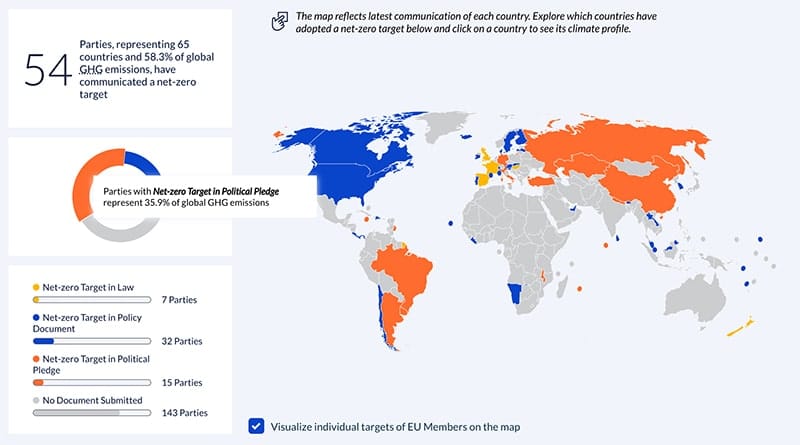

The Paris Agreement of COP21 mandated that NDCs were reviewed on a five year basis making COP26 the first review of the most up to date NDCs. So far 145 countries, representing 55% of global emissions, have submitted a new or updated NDC with 65 countries including a net zero target. COP26 will be scrutinising pledges and assessing whether they are sufficient to avoid the worst impacts of climate change. However a synthesis report of the current NDCs conducted by the UNFCCC in September concluded that whilst efforts will reduce emissions over time, “there is an urgent need for nations to redouble their climate efforts if they are to prevent global temperature increases beyond the Paris Agreement’s goal”

Source: Climate Watch - https://www.climatewatchdata.org/net-zero-tracker

The UN Environment Programme (UNEP) publishes an emissions gap report each year to show the difference between where we need to be in accordance with the Paris Agreement and where we are likely to end up based on what we are currently doing. The 2021 report – “The Heat is On” concluded that new NDCs set the world on a trajectory of raising temperatures by 2.7°C, exponentially raising the risk of substantially more poverty, extreme heat, sea level rise, habitat loss and drought (according to the IPCC’s Special Report: Global Warming at 1.5°C). UNEP states that in order to limit warming to 1.5°C by the end of the century, emissions need to be reduced by 55% by 2030, requiring submitted NDCs to reduce emissions seven times more than set out in current plans.

As well as currently falling short on policies to reduce GreenHouse Gas emissions, the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) found that nations were also not meeting finance targets for supporting lower income countries’ fight against climate change. In 2019 a total of $79 billion Climate Finance was reached, $21 billion short of the Paris Agreement target.

The current shortfalls place a particular urgency on COP26 which, coupled with the growing frequency of climate related extreme weather events, is stimulating a desire for communities to see tangible, timely and ambitious actions from their governments and organisations to tackle the climate crisis. With each passing COP meeting, the pressure to act grows as continuing rises in temperature increase the risk of irreversible changes to the climate, with efforts to prevent those changes becoming ever harder. The Youth4Climate event which brought 400 youth climate leaders from 186 different countries together captured this sentiment with 24 year old activist Vanessa Nakate saying “No more empty promises, no more empty summits, no more empty conferences. It’s time to show us the money. It’s time, it’s time, it’s time.” in her opening address.

Vanessa Nakate speaking at Youth4Climate, 2021

What to expect from the discussions

COP26 discussions will be centred around actions to secure global net zero by mid-century and limit temperatures rising above 1.5 °C. Reviews of NDCs and 2030 emissions reduction targets will be looking for plans which:

- Accelerate the phase-out of coal

- Curtail deforestation

- Accelerate the switch to electric vehicles

- Encourage investment in renewables

- Protect and restore ecosystems

- Build resilient infrastructure and agriculture

- Mobilise both public and private sector climate finance

The parties will be looking to finalise the detailed rules that make the Paris Agreement operational and in particular will be pushing for global collaboration between governments, businesses and society.

What might make COP26 Contentious?

There are a number of factors that mean negotiations are unlikely to result in swift consensus and a clear action plan.

- Not everyone agrees on what should be prioritised and how countries should work together

This is made doubly tricky by confusion on how to measure progress and what is or isn’t a sustainable investment - Carbon Markets are a bone of contention

Carbon markets, which would allow countries to receive and sell credit based on reducing emissions, are complicated to define and implement. Lower income countries also argue that credits could allow richer countries to get away with not reducing emissions by buying credits from developing countries - Not everyone agrees on reducing coal for power generation

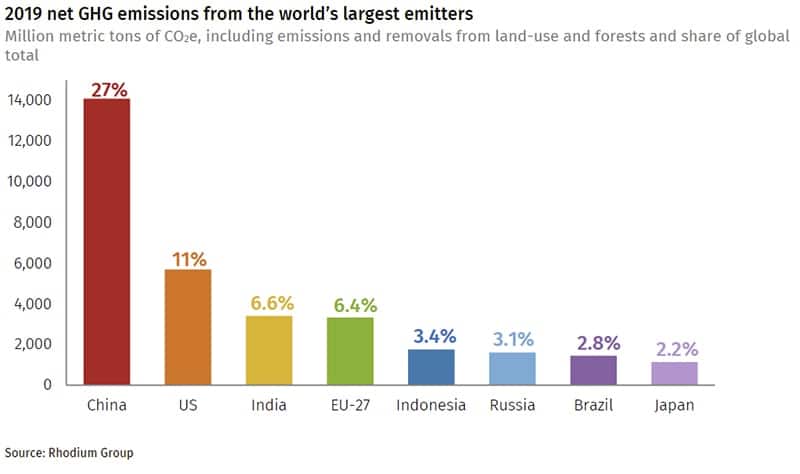

A recent leak revealed that countries including Saudi Arabia, Japan and Australia are asking the UN to play down the need to move rapidly away from fossil fuels - The largest emitters won’t be attending

Presidents Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping announced that they won’t be attending despite Russia and China accounting for 4.6% and 27% of global emissions respectively. Many feel that effective discussions and clear actions require the leaders and not just diplomatic representatives. - China and the US need to collaborate

Meeting climate goals is contingent on close collaboration. Former UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon has asked the world’s two biggest emitters, China and the US, to please find some common ground in order to drive progress and keep the 1.5 °C warming limit alive - The V20 group want to see $100 billion per year of climate finance from wealthy nations

The 20 countries who are most vulnerable to the catastrophes of climate change (V20) have urged the IMF to intervene with practical solutions to mobilise climate finance - It may not be an inclusive COP

Uneven distribution of Covid-19 vaccines globally, means many delegates from countries battling COVID-19 are unable to attend. Without some lower income nations represented, discussions and outcomes may get lower scrutiny.

What next?

Agreeing on where to go for dinner with a group of friends is rarely straightforward. Imagine trying to get consensus with 190 different groups of friends each with different dietary requirements, interpretations of what is value for money, budgets or what even constitutes ‘dinner’. It is no wonder then that discussions at COP26 will be complicated and at times contentious. However, the growing sense of urgency manifesting in an overwhelming desire for individuals, organisations and governments to see tangible and effective outputs from COP26 is something we can all find enormously encouraging and cause for optimism. Fully Charged will be watching the summit with a keen eye and will be sure to bring you everything you need to know!

About the author

Imogen Pierce works in sustainable mobility and future technology for Fully Charged and ethical AI company Bubblr. She is an alumni of electric vehicle startup Arrival where she was Head of City Engagement and Integration working with cities to understand, develop and accelerate their future mobility ambitions. Imogen has also worked in Experience Strategy looking at future technology and mobility trends. Prior to Arrival, Imogen was an aerodynamicist at Jaguar Land Rover before running the company’s technology and innovation communications. She can be found on Medium musing and wittering about sustainable mobility.