It’s been a little over a week since the COP26 President, Alok Sharma concluded negotiations on the final day close to tears. We’re asking: was this down to the quality of the deal, or the product of two weeks of small talk and a diet of lucozade tablets?

We’re now a little over a week since the 118 Private Jets soared out of Glasgow, local Airbnb prices returned from their stratospheric rates and COP President Alok Sharma shed a tear as negotiations concluded. The media dust may have settled, but the gravity of the task at hand certainly has not.

The mantra going into COP26 was ‘keep 1.5°C alive’, the temperature rise limit set out in the 2015 Paris Agreement required to prevent an all out climate disaster. Prior to COP nations’ climate pledges were due to set the world on a catastrophic trajectory of 2.4°C of warming. During the summit, Alok Sharma failed to take any breaks and sustained himself solely on Lucozade tablets in order to keep 1.5°C front and centre of the negotiations. “A rise of 1.5C is not an arbitrary number, it is not a political number. It is a planetary boundary. Every fraction of a degree more is dangerous.” Johan Rockström, the director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (Guardian).

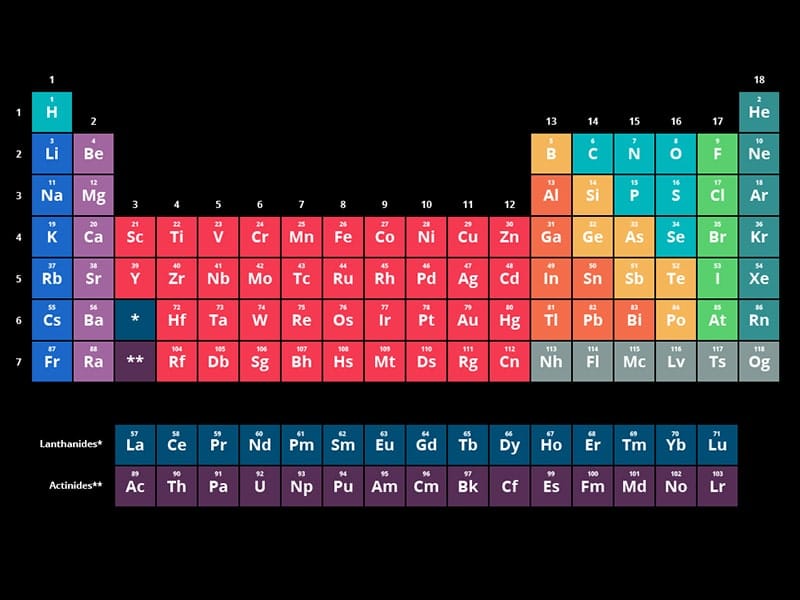

During the first week of COP, hoards of celebrities and thought leaders flocked to Glasgow to regale the importance of securing global net zero by mid-century to achieve the non-negotiable 1.5°C. At first, this seems like the equivalent of walking into a gym at 6am and shouting down a megaphone about the benefits of getting fit. However on discovering there were more delegates associated with the fossil fuel industry in attendance than any single country, and suddenly it’s as if some of our analogy 6am gym goers are simultaneously campaigning for a McDonald’s in the foyer.

Coal

The Good: More than 40 countries agreed to phase out coal by the 2030s for major economies, and 2040s for poorer nations. Amazingly (and bafflingly) this is the first time since the Kyoto Protocol in 1997 that reducing dependence on fossil fuels has been a part of COP negotiations committed to text.

The Bad: Unsurprisingly the United States did not agree to stop coal development at home but promised to halt overseas funding of oil, gas and coal. China, the largest coal producer in the world and responsible for 27% of global emissions, was conspicuously absent.

The Ugly: In the final moments of the negotiations, India (backed by China) implored Alok Sharma to change the wording in the deal from “Phase Out” to “Phase Down”. Sharma reluctantly agreed to prevent the risk of no deal.

What’s next: The International Energy Agency has said 40% of the world’s existing 8,500 coal-fired power plants must be closed by 2030, and no new ones built, to stay within the 1.5°C limit. If that’s to happen, we have to find a way for Coal to be more valuable when left in the ground.

Alok Sharma during the final stages of negotiations

Deforestation

The Good: 141 countries, representing 85% of the world’s forests, agreed to reverse deforestation by 2030 which was backed by $19.2bn of private and public funds.

The Bad: We’ve been here before and it was unsuccessful. In 2014 a coalition of nearly 200 countries, regional governments, companies, indigenous groups and others, signed the New York Declaration on Forests calling for halving deforestation by 2020 and “striving” to end it by 2030.

The Ugly: Deforestation is often caused by removing trees to make room for animals to graze or other food products such as cocoa, soya or palm oil. Plans to improve biodiversity and reverse deforestation can’t be made separately from considering food generation, consumption habits and agricultural trade.

What’s next: Understanding where funds are going and policing deforestation will be tricky. Selling food and goods to consumers in wealthier nations must become less compelling than striving for sustainable land use. International goals and policies on this front will be paramount to enabling resilient communities.

Methane

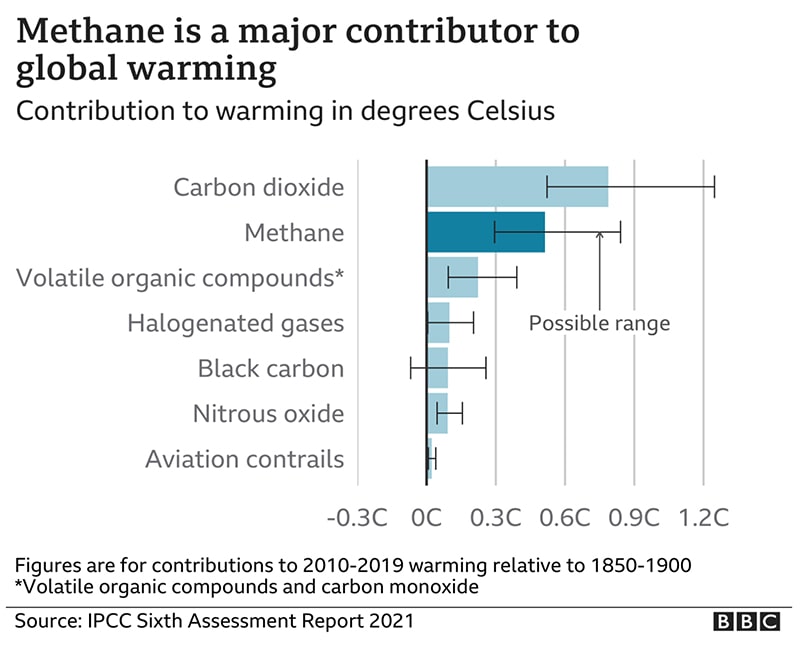

The Good: 105 countries promised to cut their methane emissions by at least 30% by 2030. Methane warms the planet 86 times as much as CO2 according to the IPCC and could reduce warming by 0.2°C by 2050 if the goal is met.

The Bad: Once again China did not join the pledge, and this time was joined by Australia, Russia, India and Iran. With just voluntary commitments it is unclear how businesses will be incentivised to reduce methane emissions.

The Ugly: Methane is emitted in coal and gas production, as well as from livestock, agricultural activity and breakdown of organic waste. As a result the pledge applies pressure to both the fossil fuel industry and farmers. The latter claim that there are fewer technologies and investments in methane reducing innovation compared to CO2 and so the transition will disproportionately hurt the farming industry. Additionally, farmers who currently benefit from carbon offsetting by selling credits to plant trees, would have to offset their carbon instead.

What’s next: Given Methane’s potency, tackling methane is at least a nod towards the severity of the climate crisis and the urgent need to make big changes. The 105 countries that did sign the pledge represent 70% of Global GDP and can hopefully kickstart more agricultural innovation.

Transport

The Good: Governments, businesses and other automotive organisations promised to work towards all sales of new cars and vans being zero emission globally by 2040, and by no later than 2035 in leading markets.

The Bad: Just 37 countries signed the pledge, a disappointingly small list that was missing some of the world’s largest auto markets including US, China, Germany, South Korea and Japan and two of the world’s biggest manufacturers, Toyota and Volkswagen.

The Ugly: The efforts to curb emissions from aviation, buses, HGVs and investing in rail were comparatively lack lustre. As was evidenced by the temporary COP26 Glasgow integrated travel card given to delegates, there is a need to look at transportation systems more holistically such that clean public transport is always a more viable option than any other mode of transport.

What’s next: Electric Truck maker Rivian went public last week with a market value of $115bn, a staggering value that would have been unimaginable 5 years ago. The growing consumer appetite and options from manufacturers coupled with the long list of cities, fleets and industry bodies who did agree to the targets shows there is plenty of cause for optimism for transportation.

Rivian recently listed on the NASDAQ raising $11.9bn

Carbon Markets

The Good: After 6 years of wrangling, the so-called Article 6 rules for a new global carbon market were put into place. This establishes a framework for the trading of credits that represent a tonne of carbon that has been reduced or removed from the atmosphere. The current system is regarded as opaque, fragmented and unregulated which also allows for double counting of emission savings. The new rules lay the foundation for existing markets to link up and allow carbon markets to operate globally, potentially enlarging the money-making opportunity of reducing carbon emissions at speed and scale.

The Bad: Many countries and politicians would still prefer for the market to manifest in the form of a tax such as a carbon border tax which would require importers to pay a price for the carbon impact of energy-intensive goods, regardless of where they were produced. This could cut emissions and level the playing field for local manufacturers and prevent lobbyists from the fossil fuel industry gaming the system and profiting from it.

The Ugly: A compromise in the new framework would allow old credits created under the Kyoto Protocol into the system. The old credits, sometimes called Zombie Credits, are considered unreliable and not reflective of the climate benefits they claim.“Sadly, the zombie credits have been given renewed life and could continue to be used for the next decade, cleansing climate targets on paper but spoiling the atmosphere in reality,” CMW Policy Officer Gilles Dufrasne.

What’s Next: Money makes the world go round and whilst there are sure to be teething issues and iterations, any signals that show emitting CO2 won’t be profitable should be welcomed. Creating new market structures is bound to encourage the private sector to ramp up green investment and accelerate the race to net zero.

Climate Finance

The Good: The Glasgow Climate Pact includes a commitment to double ‘adaptation finance’, funding to help the lowest-income countries improve climate resilience, to $40 billion by 2025. Adaptation finance is around one-quarter of the $80-billion climate finance currently available every year to low- and middle-income countries

The Bad: Wealthier nations are still to reach the $100bn a year target to help poorer countries affected by climate change, and it is now estimated according to the UN’s IPCC that it will take a trillion dollars a year to deal with the losses caused by climate change. However, they did nobly*** commit to continue working on a definition of climate finance that would be acceptable to all countries…

The Ugly: Nations failed to agree on whether to create a “loss and damage” fund, that would compensate climate-vulnerable countries for damage resulting from emissions that they did not create. The COP26 deal does however include plans for an office connected to the United Nations that will continue to research the idea.

What’s Next: The poorest nations and island nations are the world’s barometer offering us alarming glimpses into a future enabled by lack of action. Tuvalu’s Foreign Minister delivered his speech knee deep in the ocean warning that by the end of the century the island could be completely underwater. In the race to net zero, delivering on commitments is paramount to building trust between the most vulnerable nations and the biggest emitters.

Simon Kofe – the foreign affairs minister for Tuvalu delivered a speech knee deep in water

So what?

COP26 may have arrived at a fragile deal, but it did manage to ‘keep 1.5°C alive’. Just.

However, COPs are never going to be the game-winning penalty, nor should they be. It was a pre-match pep talk with the under 11 b team training to play Real Madrid. That said, reading the Glasgow Climate Pact, it is filled with language like ‘urges’, ‘encourages’, ‘welcomes’, ‘emphasises’ – words more fitting for a croquet match, not the Champion’s League.

The Under 11 B team playing Real Madrid may sound like such a predictable failure it wouldn’t be worth playing. But it doesn’t have to be. Today, 90% of the global economy is now covered by net-zero goals, $130 trillion of private sector finance has been pledged to achieve net zero emissions by 2050, China and the US have agreed to cooperate on climate change, the next 1000 unicorn startups are likely to be in climate tech – all of these actions provide the right incentives to make tackling climate change not just the sensible, scientific and moral thing to do, but the profitable one too. Suddenly, this team of Under 11s has the ability to be a team of undiscovered Lionel Messi’s. I suggest we back their chances and invest in their training.

About the author

Imogen Pierce works in sustainable mobility and future technology for Fully Charged. She is an alumni of electric vehicle startup Arrival where she was Head of City Engagement and Integration working with cities to understand, develop and accelerate their future mobility ambitions. Imogen has also worked in Experience Strategy looking at future technology and mobility trends. Prior to Arrival, Imogen was an aerodynamicist at Jaguar Land Rover before running the company’s technology and innovation communications. She can be found on Medium musing and wittering about sustainable mobility.