On 29th August 2019, This Is Money ran an article that claimed that electric vehicles depreciate up to twice as quickly as petrol or diesel cars. Nothing could be further from the truth.

They had taken their information from a flawed piece by DoneDeal.ie, who later admitted that they had forgotten to take the UK Government’s £3,500 electric vehicle grant (which was previously an even more generous £5,000) into consideration. The This Is Money article subsequently disappeared without a trace, but many people who read it will now have taken its message as gospel. So what is the reality with electric vehicle residual prices?

Electric vehicle residual values in the UK have been interesting to watch over the past few years, and nothing quite epitomises the story like the Nissan LEAF (such as the 2014 UK-built model that I own). When the LEAF first hit the UK market in 2011, it cost approximately £26,000 after the government grant was deducted. Over the following five years, a handful of competitors were launched, including the Renault Zoe, BMW i3 and Tesla Model S. Nonetheless, there wasn’t much electric competition for the LEAF. The range of brand new EVs gradually improved, with the 30 kWh LEAF, launched in 2016, pushing non-Tesla EVs over the 100-mile-per-charge threshold. Meanwhile, the original, pre-2013, Japanese-built 24 kWh LEAFs started to suffer accelerated battery degradation in hotter climates such as California; this was remedied in 2013 with the UK-built Mk 1.5 LEAF, which still had a 24 kWh battery pack, but this time with a much more heat-resistant and longer-lived chemistry. Whilst heat was less of a concern in Britain, a combination of longer-range EVs and concerns about battery lifespan served to push the residual value of the 24 kWh LEAF – including the heat-resistant UK-built ones – to their lowest point of £6,500. The residual value of the Mitsubishi i-MiEV and its Peugeot and Citroen counterparts sank to £4,000, and used Renault Zoes had little residual value since most second hand car buyers didn’t want to spend upwards of £70 per month on the battery lease.

Residual value for the 2014 UK Nissan Leaf

Then something interesting happened: residual values started increasing, and fast. By 2017, buyers struggled to find a 24 kWh LEAF for less than £8,000, and a year later, the same vehicle, now a year older with even more miles on the clock, would easily fetch £10,000 or more. In fact, the residual value of the oldest and shortest-range EVs shot up by 50% on average between 2016 and 2018. Even today, a 2012 Mitsubishi i-MiEV is worth £6,000. Compare and contrast this with diesel residual values, which have tanked in the aftermath of Dieselgate.

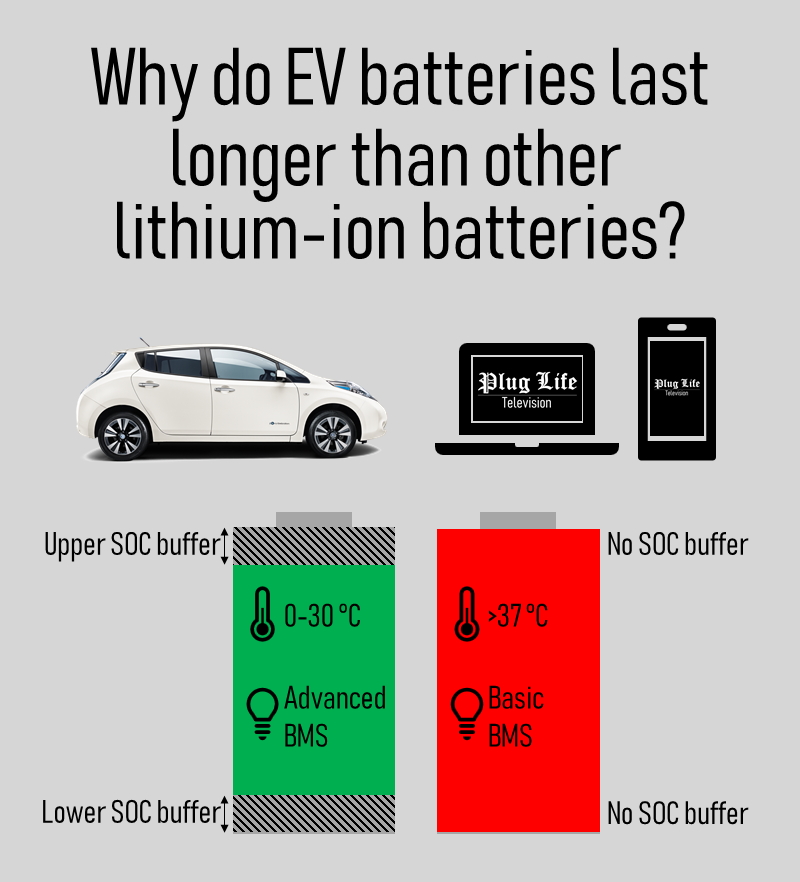

The second hand EV price rise has been driven by a couple of major factors. Firstly, concerns about battery life have been well and truly disproven. Many people initially thought that the lithium-ion batteries in electric vehicles would last about as long as they do in consumer electronics, i.e. about three years. However, electric vehicles have far superior battery management systems (control electronics that ensure that the cells don’t reach too high or low a voltage or temperature), and thermal management systems which keep the batteries at their optimum temperature. Additionally, most electric vehicles have upper and lower State of Charge “buffers” that lock out the top and bottom few percent of capacity, which helps to prevent electrolyte degradation at high SOC and overdischarge if left for too long at a very low SOC. In other words, when your car’s dashboard says that the battery is fully charged, it is really only about 95% charged, which makes a big difference in increasing the battery’s lifespan. Compare this to phone and laptop batteries: these operate at high temperatures and voltages, with no SOC buffers, so degrade quicker. As such, EV batteries are lasting much longer than early armchair critics had suggested. A glittering example of this is Wizzy, the 24 kWh Nissan LEAF taxi from Cornwall, which clocked up over 170,000 miles on its original battery before being sold to its new owner; that’s more miles than most petrol or diesel engines do without encountering serious problems. Incidentally, the only mechanical repair that Wizzy required over those >170,000 miles was one ball bearing.

Why do EV batteries last longer than other lithium ion batteries

Secondly, electric vehicles started to reach the attention of the wider public. As more and more electric vehicles and charging networks launched, and advertising campaigns became bigger budget, more people started talking about electric vehicles. Advances in battery tech had now resulted in multiple electric vehicles that could do close to – or over – 200 miles per charge, making them an even more attractive proposition. Engaging with the first generation of modern EV owners generally sealed the deal and convinced people to take the plunge and go electric. However, not everyone could afford a new EV outright, and not everyone wanted to get an EV through a lease or PCP. Furthermore, as surging demand created year-long waiting lists in some cases, not everyone could quickly get their hands on a new EV in the first place. As a result, an ever-increasing number of people turned to the second hand market, where there was also limited supply. As with any commodity when demand outstrips supply, this pushed residual prices up on the oldest models, whilst the value of newer and more expensive variants held steady.

One of the last of the older generation of EVs to experience this price surge was the Renault Zoe. As people began to scramble for whatever EV they could afford, or the least expensive EV in order to take the plunge and give it a go, the fact that the Zoe’s battery rental cost the same for a used model as it did for a new one suddenly became less of a concern. The EV sales specialist Nick Raimo (@raimonick) who sold one of my family members a Zoe halfway through its meteoric price rise later lamented that he could buy it back from them for more than they paid for it, and with more miles on the clock, and sell it on for a profit.

This is all good news for UK EV owners: a 377% year-on-year surge in EV sales in August means that demand is continuing to grow at an exponential pace, with the second hand market being no exception. But is this pricing some people out of the market? Not if you run the numbers. By taking out a five-year low-interest personal loan (based on the best rate that I could find online at the time of writing), the total monthly repayments, car tax (which is free) and electricity bill for a Mitsubishi i-MiEV, doing 1,000 miles per month and recharged at home at 15p/kWh, are as little as £146.09, or £108.59 if you have access to free charge points. This compares to £136.50 in monthly fuel bills alone for the cheapest petrol car on Autotrader, assuming a generously low £1.20/litre. Even with the residual price surge, EVs are affordable for many motorists. Furthermore, if you’re lucky enough to live in Scotland, Transport Scotland’s six-year interest-free EV loan is about to be opened up to second hand EVs too, which should bring the monthly repayment down to £83.33.

So electric vehicle residual values are stronger than they’ve ever been, but what happens when the battery eventually reaches End of Life? “End of Life” for an EV battery does not mean that it is completely dead; depending on the manufacturer’s definition, it still has 70 to 80% of its usable capacity left. In older, shorter range EVs, this is potentially the difference between the car being usable for your commute or not, but in most modern EVs, that’s still upwards of 100-150 miles (or more) of range left in the battery. If that range isn’t useful to you, it’s definitely useful to plenty of other people, so the car, with its original battery, still has value. Besides, most EVs have eight year battery warranties anyway, so buyers of new and second hand EVs have peace of mind.

If the battery reaches “End of Life” after the warranty has expired, there is still residual value in the battery or “Second Life” applications, such as grid storage, and there are multiple options to replace the car’s battery. Firstly, the battery could be replaced by the car’s manufacturer. For example, Nissan offer 24 kWh battery pack replacements for the LEAF, which cost about £4,500 for a brand new pack or £3,000 for a refurbished one. Secondly, independent EV specialists, of which there are many in the UK, would likely undercut the manufacturer’s quote to replace the battery; the Hybrid and Electric Vehicle Repair Alliance (HEVRA) will be able to put you in touch with many of these firms. Finally, on many EVs, the battery capacity can be upgraded during the replacement. BMW and Renault have been known to offer this service in some European markets, nearly doubling the range of their older vehicles in the process. Electric vehicles are mechanically robust due to their small number of moving components, so repowering an old EV with a new or refurbished battery pack is a financially shrewd move since their drivetrains will easily outlast anything with an internal combustion engine in it.

In summary, the surge in demand for electric vehicles is ensuring that new models have some of the most attractively low depreciation levels of any vehicle, whilst older models have seen a substantial rebound in their residual value of up to 50 %. Cell chemistries and battery designs that are better than those found in consumer electronics have resulted in electric vehicle battery packs outliving expectations and keeping residual values high. Despite this, it is still cheaper to buy and run a second hand EV than it is to run an older petrol or diesel car, and if you don’t have the cash up front, there are other ways and means of getting into an EV affordably. Whether you’re a prospective or current EV owner, driving electric puts you in a far better financial position than driving a gas guzzler.

Find out more about Plug Life Television.